Grottoli team discovers that coral survival in a changing climate is linked to their microbiome

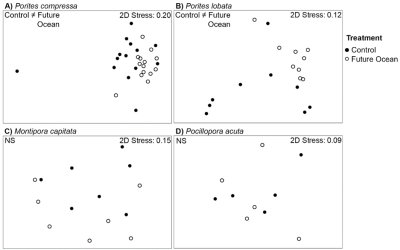

Much like the gut microbiome in humans is associated with human health, the coral microbiome appears to play a role in coral health. The Grottoli team in the School of Earth Sciences conducted a 22-month long experiment on four Hawaiian coral species (Porites compressa, Porites lobata, Montipora capitata, and Pocillopora acuta) to evaluate if the microbiome helped coral survive chronic long-term exposure to ocean warming and ocean acidification – conditions meant to mimic predicted end-of-century ocean conditions (Fig 1). Her team found that the coral microbiome responded in one of two ways: (1) the microbiome changed in P. compressa and P. lobata corals allowing them to acclimatize to future ocean conditions, or (2) the microbiome did not change in M. capitata and P. acuta and was pre-adapted to future ocean conditions (Figure 2). Both strategies were associated with survival. Thus, some species need to shift their microbiome to survive, while others may already have individuals with microbiomes that confer stress-tolerance. These findings suggest that the coral microbiome plays an important role in the persistence of some corals and could underlie climate change-driven shifts in coral community composition over the coming decades. This work was led by recently graduated SES PhD student Dr. James Price and co-authored by another recently graduated SES PhD graduate student Dr. Rowan McLachlan. The full citation and open access publications is Price JT, McLachlan RH, Jury CP, Toonen, RJ, Wilkins MJ, Grottoli AG (2023) Long-term coral microbial community acclimatization is associated with coral survival in a changing climate. PLoS ONE 18(9): e0291503. The paper is available for free download here. Visit the Grottoli lab webpage for more information about this and other ongoing research projects.

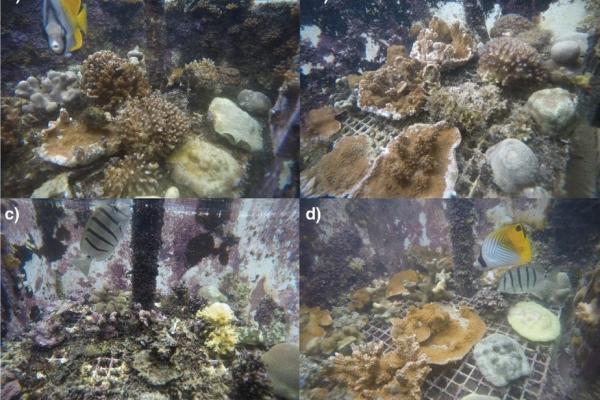

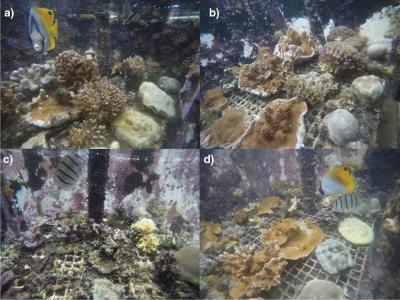

Fig 1: Representative photos of the experimental tanks after twenty-two months of exposure to: (a) control, (b) ocean acidification, (c) ocean warming, and (d) future ocean treatment conditions. In total, there were 10 tanks of each treatment.

Fig 2. NMDS plots of coral-associated microbial community composition between the control (closed circles) and the future ocean treatments (open circles) for corals of each coral species that survived the future ocean treatment.